Text © Richard Gary / Indie Horror Films, 2015

Images from the Internet

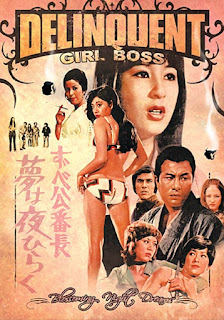

Stray Cat Rock: 5 Disc Set

Hori Productions / Nikkatsu

Arrow Films / MVD Visual

Stray Cat Rock: Delinquent Girl Boss (aka Nora-neko

rokku: Onna banchô)

Directed by Yasuharu Hasebe

81 minutes, 1970 / 2015

Rumour is that Roger Corman based his

motorcycle films on this one, though there is also a strong indication that DGB was influenced by the likes of Riot on Sunset Strip (1967). However, I

question that, considering he directed The

Wild Angles in 1966, four years before this one. The mixture of topical

music artists and the independent crime/drug genres are blended seamlessly,

with one of the main characters being the throaty Ako played by pop star Akiko

Wadda. She stands nearly a head taller than most of the rest of the female

cast.

Mei (Meiko Kaji), who would become

the star of the rest of the series, is the leader of a bunch of tough women

called the Stray Cats (or Alleycats, depending on your translation). She

dresses what you might imagine Peggy Lipton wearing on “The Mod Squad,” (1968-73)

or Pam Grier in Foxy Brown (1974), such

as a loose fitting brown suede pants suit. In other fashions, there are a lot

of multi-colored sunglass lenses, including blue, yellow and tan. Speaking of

which, I ask this as an honest cultural question, as I simply don’t know. Do

gangsters or motorcycle riders tend to wear tan pants in Japan? Or is it

supposed to reflect the uniformed worn by the film’s crime syndicate? More on

that later, but, ah, makes me wonder…

The exception in this crowd is Ako,

who dresses in leather as she drives a motorcycle, yet she still joins up with

the group. I’m not sure if the title refers to her or Mei, honestly, but then

again, I’m more concerned about the story in general than any specific thing

like that. When one is watching a foreign film, especially from an Asian

country, you have to accept that the translation into English is not going to

be exactly accurate, so you go with the action.

A right wing nationalist syndicate

comes into town (they dress like soldiers), and joins up with a male motorcycle

gang since their leader of the hog riders is the brother of the crime group capo.

The Don, as it were, looked familiar and then I realized it is Tadao Nakamaru:

he played Shephard Wong, in What’s Up

Tiger Lily? (1966). As in most Japanese gangster films, they are up to no

good. For example, they try to buy off a boxer to throw a fight, but thanks to

Ako egging him on, as well as Mei’s boyfriend being the one who convinced him

to throw it in the first place, he KOs the opponent. This leads to trouble since

the syndicate lost a lot of smackeroos, so they take it out on the b/f.

Hitting him with Aikido sticks, the

women come in and rescue him, and now the syndicate is after the ladies, as

well. One of the vehicles the syndicate drives, a Fellow Buggy, has an Ohio

plate, perhaps a nod towards Kent State University, which was still fresh on

the news? Okay, I won’t talk about that the plate is from 1961, especially since

on the back are two plates, from Florida and another from Texas. Perhaps they

were predicting the bushwhacking Bush brothers’ 2000 election. A bigger

question is why would a vehicle belonging to a nationalistic Japanese gang have

US plates?

Music has a much to do with the film,

mostly indirectly. For example, there is a Lot of jazzy sax playing over the

action, like many cool movies did in the States in early-to-mid-1960s to indicate

toughness, sexiness or socially Outsider action. Also Akiko gets to sing a

couple of numbers, one from a club’s stage, and the other in a more musical

film way, singing about how “girls are girls.” Another band at the club, which

is nowhere near as raucous as the Chocolate Watchband, is called Ox; no, there

wasn’t any sign of John Entwistle.

And in the realm of the senses of

stream of consciousness, here are some quick thoughts: there is a chase scene

in here, through subways and over walkways, and I must say it’s one of the more

silly ones I’ve seen , though not anywhere near as purposefully bizarre as The Blues Brothers (1980). The Ako character

is very butch, but this is 1970, so in one scene they have her drooling over

pretty dresses in a storefront window; gender politics, indeed. The ending,

especially the final shots, is right out of an Alan Ladd Western.

Overall, it was very ’60-‘70s Corman,

or more accurately reminded me of Jack Hill’s Pit Stop (1969), though not as gritty nor noir. It was a good ride,

and a fine place to start on the quintuple series.

Stray Cat Rock: Wild Jumbo (aka Nora-neko rokku: Wairudo

janbo)

Directed by Toshiya Fujita

84 minutes, 1970 / 2015

Five minutes into this second in the

series, and I can already see four commonalities. First, there is, of course,

Meiko Kaji; second is disenfranchised

youth at a crossroads; third a Buggy, though different from the first film,

and; fourth is an almost immediate Coke product placement (in both films, pop

singer Akiko Wadda plays a female motorcycle rider; in this one it’s a cameo, where

she drinks a bottle at the beginning).

The gaggle group of early

20-year-old-or-so are poor and call themselves the Pelican Club, and share a

room in a poor, industrial part of the city; the junk yards and debris is

another element in common with the first film. Even though they like jazz, as

evidenced by the album covers that cover the walls of their second-floor shack,

they are less likeable than the Alleycats. They think nothing of driving dangerously

with an overcrowded Buggy cab, or shooting out the tires and kidnapping the

driver of a mysterious religious group (a stand in for the right wing nationals

in the first film).

At the core of the film is social

inequity, however. Our poor shackrats have a serious rivalry going with a group

of rich kids. They run each other off the road, or go to their abodes and wreck

it. The rich kids are pricks, no doubt, as is often portrayed in films from his

era, but so are the poor ones, and it’s hard to take either side (at the time,

most likely, the viewer would probably identify with whichever social strata

s/he was in).

One of the Pelicans is a gun nut, and

finds a treasure trove of two handguns and machine gun from World War II hidden

in a school yard (oy), and the machos of the group go try out their new toys

(to keep their heads expanding, as Lene Lovich may have said). One of them, the

hot headed one, dresses loosely like Clint Eastwood in his Spaghetti Western

mode.

And then one of the crew, who falls

for the equally mysterious driver, starts dressing smartly, and moves all the

Pelicans to a resort beach to train them for... Well, I ain’t gonna tell ya,

you’ll have to see it.

This one is a bit more imaginative as

far as theatrics go, with fancy (for that time) graphics, artistic editing in

little pieces, and even some “Pow” kind of overlay, like in the Batman series (1966). However, this one

moves at a much slower pace than the first, possibly because it is hard to

identify with these young’uns. They’re sort of like a mild version of the

groups from Lady in a Cage (1964) or

especially Hot Rods to Hell (1967).

When all hell breaks loose by the end, even then it is more the music that

makes one feel any emotion than the action.

Though I wasn’t crazy about this one,

it does fit in well for the canon of youth out of control genre that was

popular from the beginning of rock and roll, right up until the early 1970s

(arguably brought back again for 1995’s Kids,

if not 1979’s Rock and Roll High

School). It is okay for a laugh, as is much of the genre, and it fit

somewhat comfortably into the formula. That being said, I envisioned a

different ending, so in that way it made me happy.

Stray Cat Rock: Sex Hunter (aka Nora-neko rokku: Sekkusu

hantaa)

Directed by Yasuharu Hasebe

85 minutes, 1970 / 2015

While we once again are introduced to

a variation of the female Alleycats girl gang in opposition to the male Eagles

group, this film tackles the social schema of race relations. Taking place in

Yokosuka, there a U.S. Naval base is located there since post-WWII, and

especially because both China and Russia are right around the corner (“I can

see Russia from my house!” said Tina posing as Sarah). The end result was a lot

of mixed race Japanese with both Caucasian and Black American fathers. These

offspring were treated about as well as Blacks were treated in the Deep South

in the 1950s, seen as unpure.

As we meet the two gangs, they both

start out somewhat on the same team, with Mako (Mieko Kaji) leading the ‘Cats,

and Baron (Tatsuya Fuji, who would star in In

the Realm of the Senses in just six years) heading the uber-macho Eagles.

Despite some co-mingling (i.e., sex) and sharing of drugs (hash and pot, from

what I could see), one of the ‘Cats turns down advances from an Eagle because

she is in love with one of the Japanese / Black sires. This infuriates the birdbrain

because (a) her love interest is mixed,

and especially (b) it isn’t him.

The poor guy is beaten to a pulp by

the Eagles, and he is defended by Kazuma (Rikiya Yasuoka, d. 2012), another

mixed-race guy in one of the worst fight scenes I’ve seen in a while. I don’t

think I’m giving anything away in that the filmmaker is obviously setting up

Mako to become a love interest with him.

Baron and crew decide to war against

the “half-breeds” because he doesn’t want them touching “his women.” But you also know that there will be hell to pay with

Mako and crew. As the leader of the ‘Cats, this is by far the coolest Kaji has

looked to date with long, flowing pants and wide-brim hat (again, reminiscent

of Pam Grier, who apparently was the model for what is “cool” in this films).

Of course, in a perverse sense of irony, the guys all drive around in U.S.

jeeps.

Yeah, the Eagles are definitely winners in the gene pool, not only

picking on people, as gangs are wont to do, but it’s always the entire group of

a dozen guys picking on a single one. No balls at all, but typical of the

mentality of these kinds of films.

But as much as this film is about

race, it’s also about gender, with the men being possessive of the women,

dealing in human trafficking to the “Harrys” (Westerners and Europeans), and

assuming all women are “bitches” (again, taken from the language presented).

But obviously, they underestimate our dear Alleycats. And you know it is going

to lead to a showdown at the ol’ corral.

While this feels like the most

complete of the films so far in the series, it is also a very unsatisfying

ending for me. I was expecting more of it than some posturing macho stupidity.

There was so much more that could have been done to make it complete, but this

was 1970, not 2016; if this were made now, after a span of 45 years of ever-stronger

women, this certainly would (and should) have a more meaningful ending.

One last comment is that, thinking

collectively again, there are some elements that these three films had in

common: first, women who drive motorcycles (the only one that does not stand in all five, as the last one

women are on bicycles, but I jump ahead); second, a vehicle driving down steps;

and third, lots of Coca-Cola placements. Sure, there’s a Pepsi sign in there

too, but it’s mostly Coke. The last is music. Lots of then-modern music with an

acid rock or blues touch. For live sounds, there is the girl pop group Golden

Half, made of equally Eastern and Western members, all singing in Japanese.

Nice touch considering the divide between cultures in the rest of the story.

Stray Cat Rock: Machine Animal (aka Nora-neko rokku: Mashin

animaru)

Directed by Yasuharu Hasebe

82 minutes, 1970 / 2015

With her wide-brimmed

Clint-Eastward-No-Name cowboy hat hanging over her back, Maya (Meiko Kaji) is

the head of the Yokohama girl gang to whom we are introduced even before the

credits, revenging a near rape the night before by a group of foreign sailors.

Joining them is another male gang,

the Dragons, and they take off, only to stop and harass two guys from out of

town who are apparently having car trouble. You feel sorry for these two as maroons until we learn that they are

actually good guys trying to sell 500 hits of LSD to pay for a boat to get an

American ‘Nam deserter buddy (as well as themselves) on a boat and outta Japan to

Sweden. And that is where the clash of the male gangs begins, with our ladies

in the middle.

How do the ‘Cats get involved? First,

by stealing the car with the hits, and then becoming sympathetic to their

cause. Then it’s them against the bad boy Dragons, led by the sidecar riding Jerry

Lewis (sans funny) looking Sakura (Eiji Go). No one seems to be able to hold on

to the drugs very long as it either gets lost, stolen, taken, or sold out from

under. Then there is the real head of the Dragon gang, a purple-obsessed and

wheelchair bound woman named Yuri (Bunjaku Han; d. 2002). Will she take the

sisterly side of the women in the gang? Will the bi-gender-segregated gangs

sort it out? Will the drug sellers and “deserter” get on their boat?

Well, it’s Japanese cinema, the Game of Thrones of its time, and you

never know who is going to live and die. I will tell you, however, despite the

lack of Coke logos (though Honda is prominently mentioned), there is the

inevitable scooter chase through the back alleys, ship yards and factories (as

well as restaurants). My, how cell phones would have changed these stories.

Over jazzy music that reminds me,

again, of Hot Rods to Hell and other

youth exploitation films from the period play over scenes of people running

around, or in Easy Rider (1969) mode

of montages of the gangs riding cycles, cut with weird editing, like the screen

split horizontally to show concurrent actions, or wiping across. This is both

imaginative (even if borrowed) and in the pre-digital days, not an overly easy

process.

There is also a lot of music in this

film; with so many scenes taking place in a nightclub, it gives the audience a

chance to see some live groups and singers lip syncing their songs, and even a

character or breaks into a song at an emotional point, as does the angst-lyrics

number by Kaji as she philosophies with the LSD dealer, Nobo (Tatsuya Fuji; his

name is shortened from “Nobody”). He and his friends also want to escape to the

West from the ennui that has set in on post-WWII semi-occupied Japan.

The language (translation) of the

film is interesting, with lots of uses of the term “chicks” and “rednecks,” and

other terms that were then hip/now outdated. How accurate it is done, again, I’m

not sure. I mean, there could be a Japanese slang term for women that would

make no sense translated directly; after all, would Japanese terminology

understand that “a tomato” at one time was a slang term for females? My guess

is the translation from the film is more Western cultural than literal.

But there is also a political aspect

to this one, too. With the Viet Nam war coming around the bend to a conclusion

in just a few years, and the pressure on by the counterculture, the topic was –

er – topical and hot. Various characters have definite opinions on deserters,

even if it was by the Yanks, who were also coming to an end of their occupation

of Japan.

This film, like many of the others,

has obviously been influenced by both the realities of post-wartime occupation

and possibly the Italian Cinema of Realism, because typically in this genre of

film, you never know who is going to live or die, and there doesn’t necessarily

need to be a happy ending.

Stray Cat Rock: Beat ‘71 (aka Nora-neko rokku: Bôsô

shudan ‘71)

Directed by Toshiya Fujita

87 minutes, 1970 / 2015

As the 1970s progressed, even though

in its early stages, the psychedelic counterculture and the cinema that

reflected it started appearing outside the borders of the contiguous United

States. This would also affect the releases of other countries, including the conclusion

of this series.

The hair is getting longer, and while

drugs are more discussed in in the previous film, with brief scenes of people

indulging, here it is a bit more prevalent. There is also quite a bit more of

the straight cultural hegemonic world meeting the equivalent of Japanese

hippies in a different clash of cultures, rather than Japanese vs. foreigners

(Yanks, etc.) in the earlier releases. Also added is an element of classism,

with our hippie troupe against the corporate entity mayor, and his loyal townsfolk

(though I wonder if it’s more loyal to the power, than the person, i.e., keeping

the status quo).

While on a romp in the city of Shinjuku

with her boyfriend, Furiko (Meiko Kaji) and Takaaki (nicknamed Ryumei; Takeo

Chii) are beset upon by a male biker gang, led by President (once again, Eiji

Go), and in the melee, the boyfriend stabs one of the bikers. He’s taken away

by a very straight capo, Ryumei’s father, who is the corrupt Mayor of a rural

town. Of course, Furiko is set up for the murder and is sent to prison, where

she escapes with her sister two months later (though it’s not explained why the sister was there). From the looks of

the fence, escaping from a women’s maximum security prison isn’t all it’s

cracked up to be, like presented in films like The Big Bird Cage (1972). Throughout the film, the police’s

presence is, to say the least, minimal, and usually laughable.

For me, it was interesting watching

their version of cool-meets-uncool, a general theme in much of the Roger

Corman-esque catalog at the time, such as The

Trip (1967). For example, a straight reporter interviews and photographs our

hippie anti-heroes in an abandoned VW bus, and he is played for laughs and

derision, rather than the counterculture subjects that are meant to attract the

audience demographic.

Though aiming for the youth crowd,

there is actually less music than in the previous four films. There is a MOR

band playing in a club at some point, and Kaji sings a mournful number acapella

in a cell, but there is one near-metal group that appears on the back of a

flatbed truck for some unexplained reason for one scene. They are called the

Mops in the story, though actually they are played by the Spiders, who sing in

English.

Our protagonists are not your stereotypical

hippies, though, full of sunshine and loving peace. These guys and gals are not

afraid to fight, or use knives and guns, as they are ready to use force to get

what they want, be it Furiko or vengence.

Furiko’s group, for once, is not

segregated by sex, but an equal number of men and women. However Gender

politics definitely have a hand; although the sexual revolution was in full

force, Feminism was in its nascent stages in the West, but hardly as much in

the East. As the earlier films showed, women could be strong and in charge, but

usually only if it involved other women (other than occasional bursts of

violence against Westerners). Here, we get to see the male leader of Furiko’s hippie

group, Piranha (Yoshio Harada) say about rescuing Furiko, “The men will think

it over tonight. Then we’ll decide.” Also, during an orgy scene put on for the

reporter and his photographer, the women get nude and the men wear shorts. Woof.

But getting back to the story, Ryumei,

who has renounced his hippie ways for the corporate entity of his father, is

none too pleased to see the escaped convict Furiko show up in his town of

Kurumi. While rejecting her, she gets kidnapped by the motorcycle gang that

attacked them in the first place, taking her to be locked in a barred cell at

the mayor’s palatial estate (of course, every mayor’s estate needs to have a

caged cell in the basement, donchaknow). While the series has moved away from

the tried-and-true motorcycle gang genre, it still has a prominent place in

this story, I’m assuming for consistency sake.

I found it amusing that the hippie group

(would it be fair to call them “gang” considering some of their actions?) hide

out at an old deserved mine area (ghost town) where, as is explained in the

story, Westerns are filmed – probably that is actually true – and you know at

some point there’ll be a shoot-out. Is it a spoiler alert when it seems so

obvious? Don’t worry, I won’t comment on the fallout, but again, being the

gritty ‘70s, with the Viet Nam war still raging just a few hundred miles away

and the Cold War around the corner, not to mention the complete

commercialization (again, lots of Coke, and even the name “Ryumei” is a product

brand that sells fancy tea sets, cups, and high-end tea itself) and

industrialization of Japan reaching point of no return, things are going to be

dire. The hippie lifestyle was viewed as a direction of “No Future” before the

Sex Pistols, so expectations were low and there was negativity worldwide just

beneath the day-go surface.

|

| Meiko Kaji |

Conclusion:

As for extras, there are mostly the trailers. However, what I found most interesting was a three-part program called ”Testimony of Outlaws: Faces of the ‘70s,” a Japanese documentary averaging 30 minutes apiece, one focusing on director Yasuharu Hasebe, and one apiece on actors Tatsuya Fuji and Yoshio Harada, all of whom talk about their collaboration on this series.

Yeah, this is an extremely enjoyable set

of films, and I am happy to have finally had the opportunity to see them, after

hearing about them all these years. They are also available in Blu-Ray, so you

know the images are crisp. Whether you are a fan of Japanese cinema (though I

would say more “crime drama” than “Samurai saga period piece” genres), that

period of angst-driven culture shock, or even as a film historian, there is a

lot to mull over. Besides, mostly they are entertaining stories, even with some

of the dated politics writ large.